Death in Taurus Season

When you live in close quarters, a front-row seat to life’s end is more common than you think.

Trigger warning: Sensitive material involving human remains.

***

It was April 26, my Taurus husband’s birthday. I had planned a little party for Michael at our former apartment, a one-bedroom in a Crown Heights, Brooklyn co-op apartment building. Our three-year-old helped me put candles on the cake, and we had invited our good friend, Stacey, and her two young kids to help us celebrate.

Stacey and her kids lived in the apartment two doors down. They were Bay Area transplants, like myself, and we hit it off hard. Stacey was a stunning artist who worked part-time while raising her youngest kids. We lived in a way I had only seen on sitcoms, or heard about from older generations: we shared child care, meals, and were frequently in and out of each other’s apartments. Stacey lovingly prepared Michael’s favorite comfort food, which, as a vegetarian, I wouldn’t touch with a ten-foot-pole: extraordinary tuna sandwiches with vegetable garnishes cut like flowers. She was probably whipping one of these babies up when I called her over to smoke a joint and put some finishing touches on the birthday prep.

There was another apartment between Stacey’s and ours. It belonged to a nice older man named John. John was quiet and kept to himself. He never complained about the families living on either side of him, even though we lived with young kids in small spaces, and it could get loud. John loved us ever since the previous Christmas when Michael gifted him with a lump of hash. John had been a community activist and jazz aficionado in his younger years, but struggles with diabetes had caused him to become more reclusive as he aged.

We usually exchanged pleasantries whenever we were both entering or exiting, but I hadn’t seen John in over a week. And there was an unpleasant smell issuing from under his apartment door. A rotten smell that had begun to grow stronger in the past three days.

While Stacey and I buzzed around our apartment preparing for Michael’s little party, a man I recognized knocked on our door. It was John’s brother, accompanied by a put-together, but very elderly lady. The man asked if we had seen John, which we hadn’t. He said they were trying to gain access to John’s apartment.

As we stacked plates and put on festive music, I kept breaking to look out the front door peephole. John’s brother and mother sat on the radiator in the hall, waiting for something. After a few minutes, police arrived. We heard animated talking, and then shouts and loud knocking on John’s door. The clamor grew as we heard the door being battered open. Michael, Stacey, and I dropped what we were doing and gathered together on the couch in silence.

Shrieks pierced the noise as the police managed to pummel open John’s door. The smell of rotting flesh hit us like a ton of bricks, even through our closed door. We looked at each other in shocked silence.

Stacey’s phone rang. It was her kids, wondering if we were ready for them to come over for the birthday cake.

“Stay inside,” Stacey instructed them. “I’ll come get you when we’re ready. Please do not come out yet.”

“Why?” her fourth-grade son asked. “I’ll explain later,” Stacey told him. “Everything’s okay, but please do not go in the hall.”

Cake is a powerful draw to young children, but the two kids showed remarkable restraint and stayed inside.

Us adults in the other apartment took turns looking out the peephole. We saw workers in hazmat suits. A stretcher going into the hall of John’s apartment. Something bloated and foul-smelling, covered in a blanket, being carried back out.

John’s ancient mother in the hall, hysterical, held back by the brother. Calling John’s name again and again and again. It was chilling how you could go through almost your entire life and never encounter the worst thing about it until almost the end.

My mind seethed in memory of another body in different building. I was living in the East Village in the early nineties while a graduate student at NYU. My tenement apartment was a six-floor walk-up, and I lived on the fifth floor. One winter as I trudged up and down the stairs, I began noticing a smell on the third floor landing. It started off as sweetish and rank, and by the third day it was a nostril-burning rot that filled the stairway. I was young and only suspected what it might be. By the fourth day, I heard the superintendent talking to the police as they battered the door and dragged out the body. An elderly woman with no family or friends had died in her apartment.

John did have family, who continued to keen in the hall. How could we have a birthday party with this going on right outside our door? Was it even decent to do so?

There was a lull in activity as the police tried to gain control, intensely questioning the brother. At that point, Stacey called her kids and asked them to run the 15 feet over to our apartment for cake. Run, and do not look around or ask questions.

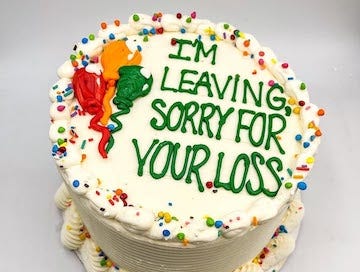

The kids did as they were told, and the six of us gathered around the cake, lighting candles. As we began to sing “Happy Birthday” to Michael, there was renewed crying and wailing from outside, drowning out our singing. “What’s going on?” Stacey’s two kids asked innocently. The adults all looked at each other, not knowing what to say. Stacey responded succinctly. “It looks like the neighbor, John, has died.” That seemed to satisfy the kids, who were mesmerized by the cake.

Although as a culture we fear death, what happened with John was perfectly normal. People who live alone die at home all the time. If you live in close quarters with your neighbors, you may very well have had a similar experience.

Death is part of life, just like birth. If someone had given birth instead of died, it would have been a miracle, handled with sympathy. Maybe the discovery of John’s body could have been sacred too. What if sensitivity-trained coroners, or municipally-employed death doulas, could be called to collaborate with police? If loved ones are present, they could be shielded from the ghastly details, and treated with compassion and dignity, rather than be grilled as if it were a crime scene and they were somehow responsible.

Michael’s birthday party was abridged that year; as soon as the hall activity petered out, Stacey and her kids went home. Michael was silent. As a Taurus, he appeared stoic, but I knew John’s final end had affected him deeply. Although not ideal, it was a birthday he will never forget.